As much as living in the city determines our existence and attitude to life, more and more tenants feel threatened. The aim of the film is thus to break through the blind fear of those under threat and present structures that make people more able to see and act. For example, an army of analysts write that it is the individual's own fault. The immense demand for living space in cities is the cause of high rents. Here, the film shows that, before the financial crisis, despite the same level of demand both rent and property prices stagnated on average and only after the crisis of 2008 did things change. Viewers experience how thereafter important investment opportunities for the rich were lost and inner-city real estate became attractive -- not least because of the zero interest rate policy, which made loans for buying real estate almost free.

Thus, the film lives from the dialectic of complicated existence and the recognition of the causes. The film’s intent is not to stir up still more fear, but to make real, livable alternatives clear. And there should also be outrage that housing as a human right is being replaced worldwide by a market that is pushing more and more people to the margins.

The film is being made in the wake of our last films Marketable People and Marketable Patients, whose success couldn’t even be stymied by the Covid 19 lockdown. Paid streaming of the films followed by discussions via conference platforms is no substitute for cinema showings. “Marketable Tenants”, the subtitle of Sold City, echoes this success and will be translated for the different language versions. Sold City will be the third part of a trilogy.

Always committed to the facts, we will strictly avoid sounding off in abstract adages. Every fact is fed by the story of the protagonists. Abstract figures are illustrated by the fate of individuals. The contrast between sterile real estate wealth and people’s growing insecurity is the aesthetic of a film that wants to create understanding and encourage people to get involved.

SOLD CITY - The marketable tenant

1 / Introduction

For more than a decade, we have been experiencing a unique real estate boom in the world's metropolises. The downside is sharply rising rents. Income growth no longer keeps pace. Low- and average-income citizens are threatened with displacement from sought-after inner-city locations. The turning point came when politicians in Europe decided to end the so-called "non-profit housing system”.

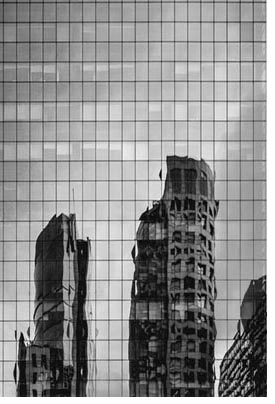

It is no longer the social purpose of housing that is the most important aspect of housing policy, but the return on investment that housing generates. Yield is the profession of the rapidly expanding real estate groups. The real estate companies  Vonovia and Deutsche Wohnen, but also LEG, ADO Properties, Covivio, Akelius, CDC Habitat, TAG Immobilien, Grand City Properties and others, are increasingly dominating the housing market all over Europe. They make record profits that industries can only dream of. The owners are anonymous pension and other investment funds from all over the world which -- in search of profitable investment opportunities – struck "concrete gold" after the 2008 financial crisis. The expectation of a return on investment is changing the urban landscape. It is not only in Paris and London that the city centres are visibly degenerating into “museums” for tourists and rich apartment owners. Neighborhoods that have evolved over time are being transformed into hip, up-market districts with the same expensive art and pub culture everywhere. Where working people stream in from the suburbs in the morning and disappear again at night because they can no longer afford to live there.

Vonovia and Deutsche Wohnen, but also LEG, ADO Properties, Covivio, Akelius, CDC Habitat, TAG Immobilien, Grand City Properties and others, are increasingly dominating the housing market all over Europe. They make record profits that industries can only dream of. The owners are anonymous pension and other investment funds from all over the world which -- in search of profitable investment opportunities – struck "concrete gold" after the 2008 financial crisis. The expectation of a return on investment is changing the urban landscape. It is not only in Paris and London that the city centres are visibly degenerating into “museums” for tourists and rich apartment owners. Neighborhoods that have evolved over time are being transformed into hip, up-market districts with the same expensive art and pub culture everywhere. Where working people stream in from the suburbs in the morning and disappear again at night because they can no longer afford to live there.

SOLD CITY not only makes the dangers for urban culture visible. It also reveals a new social question and an immense danger to democracy.

2 / The film

The film SOLD CITY will use the locations Berlin, Paris, Hamburg, Munich, London and Vienna to explore the questions of how people experience the current real estate boom, where the price increases come from and what possibilities and alternatives there are to resist them. Other films on the subject usually see it as enough to lament about the tenancy crisis. But not SOLD CITY. The film helps viewers understand why property prices and rents have risen so sharply since the financial crisis.

It shows examples, even role models, of how citizens successfully unite against this development. And it concludes that the discourse on fundamental land reform is more urgent than ever.

SOLD CITY begins and ends in Berlin. For it is here that all the points of conflict in the housing market meet, and not just in the city’s rent cap, which is unique in the world. The petition for a referendum "Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen & Co" also confuses investors.

The film takes us from Berlin to Paris, where according to the law, housing construction is still non-profit. This is quite different from London. Here, the free housing market is at its most extreme. But in Hamburg everything seems to be better, with 10,000 new flats every year. Yet the amount of social housing is steadily decreasing here too. And the modernization of low-cost flats by housing companies is closing a circle as it can only end: forced eviction from the trendy neighbourhood.

The film shows alternatives to this depressing summary. First and foremost Vienna, where the basic right to housing has been impressively realised for the majority of citizens. Or self-managed housing inspired by the Mietshäuser Syndikat. But the problem of land prices rising alarmingly is coming to a head everywhere. In German cities, 80% of new construction costs are incurred for the acquisition of building land. In the film, this leads to the final question of whether there is still a serious alternative to fundamental land reform. SOLD CITY, however, is by no means a succession of abstract adages. The fate of human beings always leads us to the cities and to housing problems.

2.1 / Berlin

A sea of demonstrators that could not be overlooked. Year after year, the already famous Berlin tenants' demos are increasingly a must for the majority of Berliners. Here, the film encounters the city's protagonists. "Deutsche Wohnen, we are not your truffle pigs," reads the sandwich board of an elderly lady named Marlies Reimann. She’s been in her flat for 43 years. Since the company took over her house, the rent has doubled, she says.

2.1.1 / Berlin / Marlies

Pankow, in Eastern Berlin. 4-storey apartment blocks from the 1920s painted in warm yellow. Marlies Reimann stands in front of her ground-floor flat and calls to her cat. "Sternchen" comes and follows her into the courtyard. An aeroplane roars low overhead. The planes are welcome, Marlies says, as protection against ever more frequent rent rises. A neighbour joins her: she has lived here since 1948, but does not know how long she will be able to pay the rising rent with her pension, meanwhile "Deutsche Wohnen" is letting everything rot.

In Marlies' two-room flat we learn that it was her first. She used to work as a waitress, but she is too old for that now. Now she has a so-called “one-euro job” in a school library. She likes her work and is popular there. She receives social welfare. But the social welfare office is no longer willing to pay the rising rents. But she’s not leaving. If she does, it’ll be feet first!

2.1.2 / Berlin / "This is our house"

The tenants of Schöneweider Straße 20 in Neukölln sing at the tenants' demonstration: "This is our house, fuck the return on investment, our pension is not enough". Their house, with two day-care centres and 40 tenants, is to be sold. The owners themselves grew up here and founded the day-care centres. An appeal to their alternative past life was of no avail in view of the prospect of a big profit, says one resident.

Visiting the courtyard party. The residents report that the threat to their tenancies brought them together. Friendships were formed, musicians met and connected. The house band plays "Our house is our home", Jan and Elisabeth -- a duo well-known in Berlin -- sing "The dream is over, but we will give it our all". Even the local mayor Martin Hikel is there. The city has a preemptive right in milieu protection areas like this one - but only at the price offered by the investor. The mayor waves it away. The real estate company's offer exceeded all affordable limits. Alternatively, he offers a so-called exemption agreement between district and buyer. This could, for example, restrict luxury renovations and rent increases. What is then eventually agreed, however, is beyond the tenants' control.

2.1.3 / Berlin / Railway flats

Berlin Neukölln, Tellstraße. These houses once had flats for railway workers. In the early 2000s, in the course of the planned railway privatization, the German government sold over a hundred thousand flats to Deutsche Annington. After also taking over company housing from EON, RWE and BIG Heimbau, Vonovia has become Europe's largest housing group. The group's strategy is called "energy-efficient modernization". This makes it possible to circumvent the nationwide rent brake. Gustel Pawlitschek from Tellstraße knows a thing or two about it. First a new heating system, then new windows, then a new bathroom, and each time lots of dust and noise. And then at the end of it all, an increase in rent, which has in the meantime more than doubled to 207%. She can only cope with this by tapping into her funeral reserves. Now Gustl is putting her hopes on the rent cap.

2.1.4 / Berlin / Rent cap

From 23 November 2020, the controversial rent cap, the so-called ban on excessive rents, will apply in Berlin. Rents will be frozen retroactively to a cut-off date of June 2019. There are exceptions, but even these will be capped at 20% above the rent ceiling. Such strict rent regulation has not existed here since 1990. Burkhard Dregger, the parliamentary party leader of the Berlin CDU, is now appealing against the rent cap to the Federal Constitutional Court. The decision is expected in May 2021. 2021. Sebastian Scheel, Berlin's building senator, is eagerly awaiting it. But even if the court overturns the rent cap, a new law will again strictly regulate Berlin's rents in compliance with the limits set -- and conflict is pre-programmed.

In an expert presentation, Vonovia promises an average rent increase rate of 4.4% per year from 2021 onwards through modernization. So far, this has only been 4.2% - but in 20 years of Vonovia, it amounts to a 228% rent increase! Rolf Buch, the company's CEO, is proud. He expects a profit of €1.32 billion for 2020 - an increase in profits despite adverse conditions. The rent cap had slowed down rent rises for Berlin flats to 0.8%. For a third of tenants, rents would even have to be reduced. But Buch hopes that the Federal Constitutional Court will throw the restriction out: "Putting a cap on rents is the same as reducing the price of bread when there is a shortage of bread." But no shareholder should be worried, Buch says -- a record dividend will be paid out.

2.2 / Paris

With Vonovia to Paris. In 2019, railway flats were also sold in France. The French railway flats were bought by Vonovia and CDC Habitat, two housing groups of roughly equal size -- which have been linked by a partnership agreement since 2017. CDC Habitat is a public company, but President Macron has instructed it to act like a private, profit-oriented group. The joint company with Vonovia is to become a pioneer in the private housing sector in France. However, the non-profit status of the housing sector still applies here. Rolf Buch is sure that this hurdle will soon be cleared.

Christophe Cariven and his wife Antoine work for the SNCF and have lived in a beautiful four-room flat for 17 years. They weren’t aware of the sale to a real estate group until the scaffolding went up. Now new windows are being installed. The Carivens haven’t had a rent increase for 17 years. Now they have received a letter telling them to accept either a graded rent contract with an overall 15.2% increase until 2026 or 10.3% on the current rent. A neighbour is trying to get them to join the tenants' association (CNL). If enough people joined, they could sue.

Only tourists

Avenue du Maine in Paris Montparnasse. When it gets dark, there are only lights to be seen in isolated flats. Flora Laconie, a judge, has lived here since birth and in her childhood saw artists like Salvatore Dali and Picasso in the neighbourhood. Local life flourished until the 1970s. But now only two flats in the judge's house are permanently occupied. All the others are temporarily occupied by wealthy tourists. Who also populate the former local pub Le Petit Sommelier. The cook and waiter have long lived in one of the still affordable suburbs, they come in the morning and disappear at night.

2.3 / London

Nobody had expected that in the midst of the greatest recession property prices in the UK would rise to a record high.

2.3.1 / London / Yield instead of living space

After 1945, Great Britain invested enormous sums in housing construction. Even in the early 1970s, half the British population lived in rented housing. Rents were affordable, there was comprehensive tenant protection. In 1988, this ended  with

with

the Thatcher government. Social housing was privatized, rent controls were abolished and fixed-term tenancies of 6 or 12 months were allowed. At the end of the contract, tenants could be thrown out for no reason or have their rents increased at will.

Whole blocks of houses in central London stand empty. In the hands of foreign millionaires or globally operating investment funds, they serve as objects for speculation. Concentrated in posh neighbourhoods like Kensington, they however also cause prices to rise throughout the city. According to a survey, more than half the tenants no longer feel safe from eviction

2.3.2 / London / Big displacement of little people.

The eviction of poor families is moving forward. The London Borough of Camden is planning to relocate 761 needy households; Brent is looking at buying cheap social housing in the English Midlands for London families. Westminster and Croydon are considering similar measures. "The market rules everything. It determines where people live," says Rueben Taylor of the action group for Secure Homes “Squash”. Thus, fewer and fewer low-income people live in the city centre.

People on good salaries are increasingly having to arrange themselves in so-called forced housing communities, like Rosie Butcher. An abandoned industrial estate in east London. Cold corridors with countless blue-painted doors. Rosie Butcher comes out of the third from the left with a sleeping bag. She doesn't even have room for it in her flat. Her furniture and belongings are in a specially rented storage unit because the place she calls home is too tiny. 17m² + a mini-balcony -- together with her boyfriend. Another couple lives in the second room of the flat. And this is by no means an isolated case.Rosie works as a research assistant at the London School of Economics. Her starting salary is a third above the average. But rents are rising eight times as fast as salaries. The two couples pay the equivalent of almost €2,700 a month for this flat.

2.3.3 / London / Hackney

Until recently, the London district of Hackney was a typical working-class neighbourhood. Today there are antique shops and restaurants with organic gourmet burgers. Signs hang outside estate agencies: "No welfare recipients". "Only rich foreigners can afford the rents in Hackney," says Rosie Butcher. She is determined to stay. Because this is where her friends live, this is where she knows her MP and this is where she gets involved. She works as a volunteer at the housing and homelessness charity "Shelter". There she met Susan. Susan has just turned 50 and has been living with her son in a tiny flat in Tolsford Road for four months. She has always paid the rent on time and the only complaint she had was the mouldy bedroom wall. The landlord then gave them notice to renovate. She would be able move back in later, but for double the rent. Article 21 of the English Housing Ordinance allows landlords "no-fault evictions".

2.3.4 / London / Criminalization of squatting

The protest against this situation lasted until 2012 with countless squats. Since then, however, the penalty for squatting has been 6 months in prison or a £15,000 fine. The government thinks it is protecting the right to property. What it has achieved is that the 70,000 or so empty houses in London today have remained unused for years. At the same time, the number of homeless people, especially young homeless people, has doubled. Simon travels around on the night bus because he can't find anywhere to sleep. The tickets are paid for by the support organization New Horizon Youth Centre. It also gives out sleeping bags and offers the opportunity to take a shower and a hot breakfast.

2.4 / Hamburg

In Hamburg on the other hand, everything seems better: more than 10,000 new flats every year. A convincing answer to the housing shortage! Unfortunately however, appearances are deceptive. 80% of new buildings are expensive condominiums and rental flats. At the same time, year after year more flats drop out of the social housing scheme than are built. 380,000 households are entitled to social housing. Most of them wait in vain. Against this background, there is now a petition for a referendum with the aim of keeping urban land in municipal hands. It demands: "Keep land and housing. Make Hamburg socially responsible". The initiative, which is supported by tenants' associations, wants to achieve that the city only grants flats and land with hereditary building rights (renting for a limited period of time). The aim is to provide social housing with permanently affordable rents.

2.4.1 / Hamburg / St. Georg

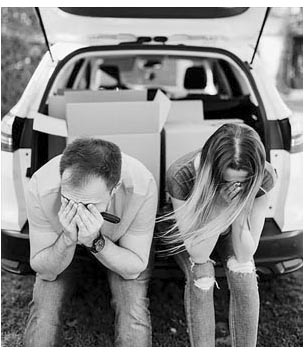

The district of St. Georg is now a hip inner-city part of Hamburg. Tourists make themselves comfortable in the cafés under outdoor heaters. They don't know that two out of  three days people lose their flats here through eviction: Michael lives in Danziger Street with his daughter Nora in a 45m² flat. A rent increase to €1,149 outrages him. He has just lost his job due to Covid 19. The landlord, the international real estate company Akelius, has turned down his request to suspend the rent increase. When Michael defaults on the rent out of desperation, he is first given notice and then evicted. On the night of the eviction, they find accommodation across the street at Nora's best friend's house. The task force arrives at 5am. Shortly afterwards, the sound of the door of the flat being broken open. An hour later, their belongings are on the pavement.

three days people lose their flats here through eviction: Michael lives in Danziger Street with his daughter Nora in a 45m² flat. A rent increase to €1,149 outrages him. He has just lost his job due to Covid 19. The landlord, the international real estate company Akelius, has turned down his request to suspend the rent increase. When Michael defaults on the rent out of desperation, he is first given notice and then evicted. On the night of the eviction, they find accommodation across the street at Nora's best friend's house. The task force arrives at 5am. Shortly afterwards, the sound of the door of the flat being broken open. An hour later, their belongings are on the pavement.

But how is it possible for Akelius to charge €1,149 for 45 m² despite the rent brake? The tenants' association gives the answer: modernization. A new bathroom or energy-efficient windows are enough to justify doubling the rent. Akelius seems to be one of the most aggressive companies in this sector. Even the United Nations has reprimanded the company for this. The group's motto is – Better living.

2.4.2 / Hamburg / Rent control brake

Housing researcher Christoph Trautvetter has systematically evaluated modernization: "The problem is the type of modernization. It is not based on the needs of the tenants but on the needs of the landlord. A new bathroom, even though the old one is still fine. This is the kind of modernization that the landlord needs to increase rents to the maximum." Between July and September 2020, 326 households are evicted in Hamburg -- 62 of them in St. Georg. Akelius, a trust based in the Bahamas, expects a return of 6% in 2020.

2.5 / Alternatives

2.5.1 / Alternatives / Vienna

Vienna, 5th district, Bärengasse. Josephine and Caspar Lugner have lived in a spacious 4-room flat in the middle of the city for 36 years. Their tenancy cannot be terminated as long as they pay the rent. The rent is €557,76 for 96m². The rent increases according to the inflation rate. What else can you say? It's a natural state of affairs, just like nice and nasty neighbours, says Caspar.

For Mayor Michael Ludwig, housing is a human right. After all, 62% of Viennese citizens benefit from it. They live either in so-called municipal or in subsidized housing. Even in  the case of privately financed flats, the city can intervene to regulate prices because of its dominant position in the market. Here the rent rarely exceeds €10 per m². However, since the financial crisis, Vienna is also aware that a great deal of private capital is looking for investment. That’s why every real estate company that buys land for conversion into housing must now build flats for a maximum rent of €5 per m² on two-thirds of the area. Only on the remaining third are they allowed to calculate freely. In addition, the city only gives building land to private investors who sell their own land in Vienna to the city. In this way, land is deliberately stockpiled. No municipal housing stock has ever been sold. No private investor could compete with Vienna Housing Fund, which has more than three million m² of land at its disposal. Martin Prunbauer, president of the Austrian Land and House Owners' Association, sees this as an expropriation of private property, which would lead to a decline in urgently needed new construction. Mayor Ludwig smiles at this. Private investment is not declining at all, he says. Despite strict regulation, there are still more purchase inquiries from private capital than the city can offer.

the case of privately financed flats, the city can intervene to regulate prices because of its dominant position in the market. Here the rent rarely exceeds €10 per m². However, since the financial crisis, Vienna is also aware that a great deal of private capital is looking for investment. That’s why every real estate company that buys land for conversion into housing must now build flats for a maximum rent of €5 per m² on two-thirds of the area. Only on the remaining third are they allowed to calculate freely. In addition, the city only gives building land to private investors who sell their own land in Vienna to the city. In this way, land is deliberately stockpiled. No municipal housing stock has ever been sold. No private investor could compete with Vienna Housing Fund, which has more than three million m² of land at its disposal. Martin Prunbauer, president of the Austrian Land and House Owners' Association, sees this as an expropriation of private property, which would lead to a decline in urgently needed new construction. Mayor Ludwig smiles at this. Private investment is not declining at all, he says. Despite strict regulation, there are still more purchase inquiries from private capital than the city can offer.

In Vienna, it is striking that there are still many shops which elsewhere are falling victim to rising commercial rents. A shop with thousands of buttons, zips and everything you need for sewing. A shop selling only wafers, junk shops, a shop with 70 different barrels of vinegar and an adjoining chicken farm. Most of them can hang on because the town is the landlord. Waltraud Karner-Kremser, chairperson of the housing committee, emphasizes that the small shops, the hairdresser, the bookshop and the café, which are within walking distance, are important for maintaining the residential value. This is also a maxim in the planning of new city districts.

2.5.2 / Alternatives / We have more when we share

Currently the syndicate has 159 housing projects. Its purpose: "The support and political implementation of new self-organized housing projects: "Decent living space, a roof over everyone's head.” The syndicate is legally involved in their projects. However, each house decides on the amount of rent, the loans and who moves in. All projects commit themselves to supporting the start-ups of others. So the newcomers can draw on a network that has 30 years of experience of self-organized housing.

2.5.3 / Alternatives / Apartment Buildings Syndicate

Currently there are 159 housing projects of the Syndicate. Its purpose: "The support and political enforcement of new self-organized housing projects: "Decent living space, a roof over everyone's head. The tenement housing Syndicate is legally involved in their projects. However, the houses themselves decide on the amount of rent, the loans and who moves in. All projects commit themselves to supporting the start-ups of others. So the newcomers can draw on a network that has 30 years of experience with self-organized housing.

2.5.4 / Alternatives / Who expropriates whom?

Berlin is a city of tenants. 82% live in a rented flat. According to research by the Tagesspiegel newspaper, half of them are afraid of losing their homes because of rent increases. New rents have doubled in Berlin since 2008. Existing rents have

risen by 40%, while tenants' incomes increased by only 15% on average in the same period. "So existing tenants are being dispossessed of 25% by their rent payment every month," says Humboldt University Professor Joseph Vogl. "When rent and land prices rise, an ever-larger share of tenants’ income is transferred to outside capital assets." Josef Vogl is a co-founder of the Berlin petition for a referendum "Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen & Co". Working groups from Humboldt University, various local administrations and citizens' groups such as Forum Potsdam initiated this petition after years of preparatory work. And their choice of Berlin was no accident.

After the First World War, the city's housing construction had been subordinated to the common good. There were absolute rent limits and from 1924 a house interest tax for large property owners. With this revenue, entire neighbourhoods were created under municipal and cooperative responsibility, in which the right to adequate housing for low-income earners applied. Examples like the Britzer Hufeisensiedlung and the city’s programme of house construction show that Berlin was once a pioneer of better housing under public ownership. These houses are still very much in demand today. After the Second World War, housing construction and tenancy law remained regulated until 1990. "Until then, Berlin was an open metropolis that welcomed everyone -- beyond stature and income. But then a market-based policy opened this field to the market and investors," explains Ralf Hoffrogge of "Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen & Co". This is how Berlin also became prey for capital from all over the world looking to invest in the city’s "concrete gold".

After the first stage of the referendum and the legal assessment, "Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen & Co" will start the second round in spring 2021.

2.5.5 / Alternatives / Land - not just any commodity

Every year, the real estate groups afford themselves a so-called value adjustment. In 2020, for example, Vonovia raised the assessed value of its properties by €1.4 billion. Their explanation: ever more expensive land prices. Former SPD leader and mayor of Munich Hans-Jochen Vogel demanded in a manifesto at the end of 2019: "Land needs a new classification". Land is not an arbitrary commodity, but a basic prerequisite of human existence -- like air and water. The Federal Constitutional Court had also stated: "The fact that land is not reproducible and indispensable forbids its use to be left entirely to the incalculable play of free forces and the whim of the individual." Almost 50 years after the late Hans-Jochen Vogel, Dieter Reiter is the mayor of Germany's most expensive city. He wants to bring Vogel's manifesto to life. The price of a square meter of building land in Munich has risen by 39,390% since 1950. That's "profit without benefits" and always  same story: "A few landowners get rich because the municipality creates infrastructure, roads or subways. So the value of the surrounding land goes up, which directly affects rents." As Reiter says, today, 80% of the costs of a new building are already incurred by the purchase of the building site. This is madness. Without a fundamental change in land law, new buildings can no longer be financed for normal income earners in the city. Land is not a commodity which can be traded. A society that wants to avoid social unrest cannot want price rises just for the sake of a hands-off approach. The land belongs in municipal hands and should then be lent for building projects via hereditary building rights. "Then we will have a host of new opportunities due to the businesses closing in the city centre. Then the rent explosion will soon be a fairy tale from market-obsessed times

same story: "A few landowners get rich because the municipality creates infrastructure, roads or subways. So the value of the surrounding land goes up, which directly affects rents." As Reiter says, today, 80% of the costs of a new building are already incurred by the purchase of the building site. This is madness. Without a fundamental change in land law, new buildings can no longer be financed for normal income earners in the city. Land is not a commodity which can be traded. A society that wants to avoid social unrest cannot want price rises just for the sake of a hands-off approach. The land belongs in municipal hands and should then be lent for building projects via hereditary building rights. "Then we will have a host of new opportunities due to the businesses closing in the city centre. Then the rent explosion will soon be a fairy tale from market-obsessed times

SOLD CITY - When housing becomes a commodity

The new "FILM FROM BELOW" by Leslie Franke and Herdolor Lorenz, 126 minutes

Here you can download the film SOLD CITY

The film SOLD CITY is the third part of a trilogy. With the subtitle “Der marktgerechte Mieter” [“Marketable Tenants”] with reference to the films Marketable People and Marketable Patients, chosen by the German TV culture magazine Titel, Thesen, Temperamente as "Best of 2020".

The film SOLD CITY will use the locations Berlin, Paris, Hamburg, Munich, London and Vienna to explore the questions of how people experience the current real estate boom, where the price increases come from and what possibilities and

alternatives there are to resist them. Other films on the subject usually see it as enough to lament about the tenancy crisis. But not SOLD CITY. The film helps viewers understand why property prices and rents have risen so sharply since the financial crisis.

It shows examples, even role models, of how citizens successfully unite against this development. And it concludes that the discourse on fundamental land reform is more urgent than ever.

SOLD CITY begins and ends in Berlin. For it is here that all the points of conflict in the housing market meet, and not just in the city’s rent cap, which is unique in the world. The petition for a referendum "Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen&Co" also confuses investors.

The film takes us from Berlin to Paris, where according to the law, housing construction is still non-profit. This is quite different from London. Here, the free housing market is at its most extreme. But in Hamburg everything seems to be better, with 10,000 new flats every year. Yet the amount of social housing is steadily decreasing here too. And the modernization of low-cost flats by housing companies is closing a circle as it can only end: forced eviction from the trendy neighbourhood.

The film shows alternatives to this depressing summary. First and foremost Vienna, where the basic right to housing has been impressively realised for the majority of citizens. Or self-managed housing inspired by the Mietshäuser Syndikat. But the problem of land prices rising alarmingly is coming to a head everywhere. In German cities, 80% of new construction costs are incurred for the acquisition of building land. In the film, this leads to the final question of whether there is still a serious alternative to fundamental land reform. SOLD CITY, however, is by no means a succession of abstract adages. The fate of human beings always leads us to the cities and to housing problems

© Kernfilm 2021